Ten out of the first 20 confirmed United States COVID-19 cases occurred in California, with the first San Diego County case reported on March 9, 2020. Within days, the county of San Diego put out a press release which said “planning now helps you act more effectively to protect you and your family if COVID-19 does spread locally”.

When elected officials and local leaders were asked what a year of hindsight has revealed, they repeatedly praised community efforts and said local measures were and continue to be far more effective than political edicts handed down from higher levels of government.

“The state and federal government certainly do have a role to play, particularly with funding, but it’s at the local level where much of the heavy lifting gets done,” State Senator Brian Jones said.

“The prior administration has taken a great deal of criticism for not nationalizing the COVID-19 response,” Jones said, but he also asserted it would be incorrect for the federal government to dictate state mandates because “that’s not how our system of federalism is set up”.

It is too easy to blame the federal government,” Jones said— he believes the way the state worked with counties is more problematic, affecting seniors, students and small business owners.

“Protecting seniors, particularly those living in nursing homes or senior facilities should have been priority one for the state at the start of the pandemic,” Jones said.

With over 12,000 confirmed deaths attributed to COVID in senior citizens to date, Jones said Gov. Gavin Newsom, in retrospect, did not adequately consult with legislators and establish a plan early on for senior facilities.

At the other end of the spectrum, students have also suffered, he said, from closures that have stretched on too long and reopenings that are defined by as little as one on-campus day of learning per week in some districts.

School officials sent students home on March 13, 2020 at the direction of San Diego County Office of Education and finished the school year through distance learning plans. Subsequently, districts began the 2020-21 school year with various distance learning, flexible and hybrid campus plans and have remained in limbo since the start of the school year.

Although some have gradually increased campus time as allowed under public health directives, the reality is that due to government orders, many students have crept through a year’s worth of curriculum without stepping foot in a classroom.

“The lost year in California students’ education is a great tragedy. We’re seeing some districts here in San Diego county who are trying to reopen but the state and union leaders are telling them ‘no’,” Jones said.

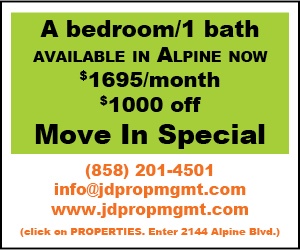

One East county exception is Alpine Union School District, a district of about 1,700 students that has offered on-campus classes in some capacity since the beginning of the school year. It is the first in the state to have every teacher vaccinated in part, Superintendent Richard Newman said, because they relied on local community ties rather than waiting for top-down directives.

“Southern Indian Health council reached out first with Viejas reservation and now Sycuan, offered to help get all our teachers vaccinated and within 24 hours, we were able to get our staff organized and slated for immunization,” Newman said, a feat that had nothing to do with county or state officials.

“We waited for the state to make a decision with coordinated strategy and they never did. We learned you can’t wait for what the state says to do, you have to figure out what your community needs,” Newman said, echoing Jones.

Prior to vaccine approval, the district worked out solutions that focused on whole families.

“From the beginning, food scarcity was huge: we started handing out meals on March 16, 2020 and we’re still trying to arrange food around our families. I had a man, with tears in his eyes, thank us for making sure his family had food and there were many nights where I felt the gravity of our role as a district, not just for students but for struggling families,” Newman said.

When a commercial freezer filled with about $20,000 worth of food slated for community distribution malfunctioned, other districts stepped in and offered to temporarily store the food for free but it would have meant turning hungry families away. Instead, Newman said, they brought in “probably $1,500 worth of dry ice” to keep the food in Alpine as the pre-pandemic goal of storing food has shifted to food distribution in a time of dire need.

“The need for internet access was another big thing. I don’t even know how many internet hotspots we’ve handed out, or Chromebook laptops for families— we really didn’t know what was behind the veil before the pandemic,” Newman said.

As the 2020-21 school year started, the district created learning pods where up to 12 students legally gathered together for distance learning under parent supervision, a structure Newman said allowed several parents to maintain their work schedule and benefited all the families.

“I relied on our local leaders when our state and national leaders had no coordinated policy or strategy,” Newman said.

County Office of Education leaders and the county public health nurses were “unsung heroes,” he said simply because they were available at any time to answer questions when state officials would not return calls.

Finally, perhaps not a new lesson learned, but a retrospective observation: politicizing solutions is counterproductive.

“Opening schools doesn’t mean you’re on the right or against a union. I think we could have had a national strategy, honest discussions that weren’t politicized all over the place,” Newman said.